Open Call Contributions

2023

mel / nuage

Jade Blackstock

GENEVA HONEYMOON

One of the things I loved about my trip to Geneva is that it is such a walkable city. Sometimes, we would underestimate the distances between the venues; though it was interesting to trace the cultural webs that Batie Festival had made via their programme and locations and spot the festival’s posters on the way. Having run to Théâtre Pitoëff and making it just on time, we were directed up the stairs. I turned around and was shocked to see my friend James Goodwin walking up. In disbelief, we greeted each other and exchanged what brought us both here (considering that he’s based in the UK, and me in Sicily). More webs, crossovers and connections. Live art and theatre festivals often remind me of how webbed and interconnected the world is and can be. And also how the liveness and ephemerality of performance encourages gathering and collective witnessing.

The first performance that drew me to the Batie Festival was Calixto Neto’s Il Faux - a solo work with dance and monologue. When looking online for a festival in Europe to attend and finding Geneva’s offering, it was the picture on the website of Neto in motion, skipping and swinging moulded brown paper that looked like flesh, that encouraged me to see what this festival was about. I had been keen to see the work of another artist whose work explored similar themes to my own. Whose main inquiry might be ‘black people - what of our bodies?’ and ‘what could refusal in search of freedom look like?’

The work took place in an auditorium with impeccable lighting. As we filed in and sat in a couple of the few extra seats that were left, I thought about how much architecture and space influences the relationships and dynamics between observer and artist. We were all facing him, expectant, as he sat on the floor of the stage, looking back at us. The work began with a monologue in French, that spoke of the black experience in Europe, racism, legacies of colonialism and other historical [factors].

There were many times that I thought everything would fall apart, but none of the elements ever really did until Neto willed it. The paper figures became a sort of army of inanimate friends, comrades. He had successfully poured the energy of himself into this paper. It felt like he had willed and succeeded in invisibilising himself from the audience - for a while, though he had literally been moving the paper figure, our eyes were transfixed on the paper person, and Neto had transcended. The paper figure had almost liquidised and become him.

Mirroring, mothering

A transmutation, a wining.

Silence - heavy breathing, attached to mic

Flow between french and Portuguese,

Jacket made of paper, outfit made of paper

“paper is a resilient material”

Mirroring, mothering

A transmutation, a wining

A transcending, the paper figure is of them

Breathing, they breathe together

Dance, hypnosis, trance, refusal, back to us

The glitch, the sweating, the questions, repitition

Satisfying exhaustion of the glitch

“no chains around my feet but, I am not free”

nomi

Niya B

Retracing the Circle: Performing Community Rituals

Everything is moving,

everything is dancing.

It’s the night of the 8th of September. I am on a 16-square-mile mass of land emerging from the Aegean Sea. Mostly rocky, with windswept low shrubs and a few olive trees.

With a permanent population of 271 inhabitants, the island lies almost at the very eastern border of the European Union and at the southern border of the Global North map. It is a land of successive colonisation, immigration, political exile, and, more recently, tourism.

I am here to observe. It’s 4:06am and we just came back after a whole night at the local festival. [1] G has already fallen asleep. I’m lying next to her, typing notes on my iPhone. The music still echoes through the village square. My eyelids are heavy, my body tired, yet my brain remains hyperactive. If I came here hopeful to resolve an internal struggle, I now find myself more confused than before.

“What is this fascination all about?” I ask myself. Is it the music, the dances, the community, the land, the sea, the tastes or the smells? When I wrote to mel, who curated Open Call, about my plan to come here, I expressed my conflicted feelings towards ‘culture’ and ‘tradition’: how they simultaneously attract and repel me. Was I secretly hoping for a discouraging response? “Go where your heart takes you,” mel wrote back.

Yet, there's the ever-present challenge of being trans. Lengthy discussions with my friend and performance artist Byuka often come back to this topic. We wrestle with our longing for certain aspects of our culture, recognising how deeply ingrained they are within us, shaping our identities. And yet, there's the constant struggle and need of escaping traditional norms – seeking belonging in a chosen community and wanting to construct our own worlds.

Still, the fascination persists: the stronger the excitement, the deeper the frustration. The more intense the yearning, the greater the sense of disconnection.

In her book on the life of the island of Anafi, British anthropologist Margaret Kenna explains that traditions emerge through the repeated enactment of specific practices, and as such, they are subject to change and reshaping. [2] While I must acknowledge the comfort in repeating familiar practices, I hold onto the potential of change.

As I’m typing these notes, the music continues in the village square. The band, composed of a female singer accompanied by a violinist and a guitar player, has tirelessly delivered the characteristic island-style tunes all night long. Repetition defines this durational performance.

The repetitive tunes bring to mind an anthropological documentary about Epirus’ musical traditions, I recently watched: Pericles in America. In the film, the director John Cohen takes us through the story of George, a Greek migrant in New York. [3] George diligently works in a cramped diamond setting workshop, isolated from his surroundings, immersed in the task he has at hand. With headphones plugged into a Walkman cassette player (it’s the mid-80s, after all), he remains cut of from his environment whilst his American boss tries to engage him in a somewhat unsettling banter – teasing him about his compulsive listening of traditional music all day long.

“He’s listening to the same boring music, the same tunes, again and again!” the boss remarks. George, focused on his work with his back to the camera, offers brief affrmations of his commitment to the music and, more broadly, culture of his remote mountainous village in North-western Greece.

I reflect on George’s unwavering sense of belonging, as we arrive at the village square of this remote island. It is 9pm and the traditional festival of the local Virgin Mary is well underway. The persistence of tradition reverberates here too – sustained by the small local population and a much larger diaspora, who resides on the island in the summer months. Tourism adds another layer of complexity to the scene.

A few tsipouros later, the typical islandic circular dances start animating, with people holding hands or each other’s shoulders at arms’ length. At the centre of the circle, a tall young woman with flowing blond hair whirls energetically with an older man, who eagerly follows her steps – their feet bouncing of the irregularly-shaped flagstones of the square.

The dance circle expands and contracts.

It resembles a breathing organism,

a pulsating heart.

A repetitive movement starts from its centre, going to its periphery and back.

Never ceasing, pushing forward,

it rotates counter-clockwise (perhaps an attempt to defy clock time?)

Ouroboros, swallowing its own tail.

The lead dancer drags this long snake-like human chain onto the earth, occasionally breaking away into a duet with the dancer next to them. As more participants join the tail or any other point of its body, the dance morphs into a spiral, circling around itself. Then, the head dancer guides the serpentine formation to thread through its periphery, where two dancers lift their joined hands high above their heads to allow passage. The dance circle undulates, interweaving the sweaty bodies until it breaks of into two or three separate dancing circles. It is a mesmerising display of movement, a multigenerational medley of bodies.

An ecstatic tune plays to exhaustion –

the loudspeakers distorting its endlessly repeating rhythm.

An old priest leads a smaller dancing circle on the side. His long, severe, dark dress flows as he moves. His dancing style reminds me more of punk-rock rather than the traditional dance steps. His fully covered arms join the naked shoulders of a young girl in legging shorts and a crop top bra. The juxtaposition is bizarre. But tonight, everything is okay.

Artist and researcher Sarah Hopfinger delves into intergenerational dance and theatre performance as an ecological practice, contending that such “human relations with each other are an integral part of our material-ecological entanglements”. [4] Perhaps, this is the reason why I am here now. In my exploration of gender and ecology, I have inevitably encountered my ancestry. And, in these encounters, I have been confronted with issues of culture and ‘tradition’.

Involving my personal perspective in my research practice follows a longstanding methodology in trans studies (and feminism), which prioritises the 'speaking' trans subject over the objectified trans object. [5] The autoethnographic approach involves examining one’s personal experiences in relation to a broader cultural and political framework. [6] It is a powerful and empowering methodology for researchers. However, I am mindful of Carolyn Ellis’ introduction in her book ‘The Ethnographic I’: “The self-questioning autoethnography demands is extremely difcult. Often you confront things about yourself that are less than flattering. Believe me, honest autoethnographic exploration generates a lot of fears and self-doubts – and emotional pain. Just when you think you can’t stand the pain anymore – that’s when the real work begins. Then there’s the vulnerability of revealing yourself, not being able to take back what you’ve written or having any control over how readers interpret your story”. [7]

It’s now 1am. I stand at the edge of the dancing circles, observing the repetitive steps, trying to decipher the choreography and its rules. Are the people who dance mostly locals? Will I disrupt their enjoyment if I join? Obviously, there are other tourists around: some of them are Greeks and, surprisingly, some others are queer.

I wear white clothes.

G is filming me.

She says: dance!

And I join.

It feels good to be part of the circle. The woman who owns the mini market where we bought groceries earlier today is next to me. I then spot the girl who works at the local taverna, where we had dinner earlier. They have just closed their shops and joined the festivities. I don’t know if they’re transphobic or not, or how they are feeling about me joining their dance. For a few moments, there’s just the dance and nothing else. A circle dance that goes back thousands of years – a sweaty language spoken fluently by diverse bodies across age, class, gender and sexual orientation. The songs and the lyrics are just a temporary layer – a performance costume draped over a pulsating body. Words are bound to evolve and change.

I want to shed this crumpling costume.

I’m dreaming of new songs – of reclaiming the circle dances.

My queer optimism is fuelled by tsipouro and the endorphin released from the dance. From initially being a quiet observer, I’m now claiming active participation.

* * *

Naturally, my presence attracts the attention of the people, who openly talk about me without any attempt to conceal it. I recall the interview G conducted with Ghanaian trans activist and artist Va-Bene Elikem Fiatsi during our art residency in Kumasi, which I filmed: “Everything in Ghana is performance” she said, “... everyone performs.” [8] I ponder this in the context of Greece: everything is performance here too. But primarily, everyone is an audience – observing one another. Performers are also spectators, and spectators perform too. People stroll around to see and to be seen. Glares are not shy: they are direct and unapologetic.

As a trans person, my appearance – which does not conform to traditional norms – is perceived as an invitation for scrutiny. But this behaviour is not unique to the locals: some retired white French heterosexual couples are particularly direct in their gaze. Whether we’re passing each other on the street, or sitting at adjacent tables in a restaurant, they turn their heads to openly study me – gossiping with each other before turning again to re- examining me. I am not sure what upsets me more: the fact that they are even more intrusive than the local Greeks or their colonisers’ gaze in my native land?

At times, I meet their gaze, directly. Initially, they seem content to hold it, perhaps hoping to uncover something in my eyes to solve the mystery they have created in their minds. But I am a professional eye-gazer – years of practice maintaining eye contact during intimate performances. Soon, they grow uncomfortable. This level of intimacy is unfamiliar to them: losing their sense of entitlement, they avert their gaze.

“Can I help you?” I ask. They smile embarrassedly, shaking their heads. After all, being on holidays on this remote island rather than in a mainstream tourist destination suggests they are of the educated, middle-class type, straight out of civilised Western Europe. Other times, I deter their unsolicited interest by turning my back, or by putting on a hat, my sunglasses, or extending my arm to block their view with the palm of my hand. Once, back in London, I even opened an umbrella in the face of a persistent starer. On rare occasions, I would blow kisses to them, inspired by my friend Asher Fynn.[9]

In the meantime, landscapes are constantly performing. The wind passing over the smooth curves of the Cycladic houses is performing. Churches are also performing. And they communicate through multi-sensory media. In the same documentary about Va-Bene Elikem Fiatsi, the artist says: "I’ve learned performance at the church."

As a child, I, too, experienced my first immersive performance shows attending masses. We’re talking about the Eastern Orthodox Church here: Byzantine hymn chanting; sermons delivered by priests with long hair and beards dressed in elaborate dresses and fancy hats; interiors with dazzling gold-plated decorations; dramatic stage lighting emanating through stained-glass windows and sparkling chandeliers; myrrh incense filling the air; candles casting flickering light; and communion with wine and bread – actual wine and bread.

* * *

The day after the festival, as we walk along the goat path from the beach, we come across a small church. In contrast to the grandeur of the churches I mentioned earlier, this one is modest, perched on the cliff's edge overlooking the sea. At its top, a blue and white Greek flag flutters in the relentless Aegean wind, engaged in a durational performance score that has literally torn it apart. Its tattered threads dance feverishly amidst the strong wind. "There's a lesson to be learnt here," I muse to G – “This nationalist performance act is self-destructing.”

I’m thinking how I’ve always felt uneasy about flags, all flags – even the liberatory ones. It’s the certainty they convey. The absence of doubt. The fixed meaning, they represent. The absolute statement of hoisting a flag or making one in the first place.

I raise my hand and examine my blue-painted nails besides the flag in the sky. The nail polish is chipped. Its condition mirrors that of the torn flag. “I’m reclaiming the colour blue from nationalism,” I declare. “The spirituality from the monopoly of the church. I stake my claim on this land of thyme, sage and sea squill. This expanse of sky and sea is not a mere backdrop for a flag.”

It’s late afternoon. The scorching sun has just set as we walk slowly along the winding path up the road. I’m not ready to see humans... I stop, crouch down towards the still-warm earth, and say to G: “I want to be with the plants.”

* * *

On our final evening on the island, we venture to a bar nestled in an old house, stripped down to its bare essentials. The room is lit solely by flickering candles. Two musicians –, one with a guitar and the other with a bouzouki – play their instruments unplugged. The woman with the guitar sings melancholic songs about broken hearts and impossible love. Most songs are well-known, and the familiar tunes feel comforting. G enquires about the lyrics. In translation, the melancholy seeps into me. Besides us, twenty-year-olds sing along, swaying languorously their heads to the music while indulging in warm rakomelo and other liquors. They draw deeply from their cigarettes, killing their lungs with the hot tobacco smoke as a remedy to the unbearable vitality of their being. The singer asks the bartender to fix her a drink. G asks: "Did she ask for water?" "No," I reply, "she asked for black rum on ice."

* * *

The next morning, as we’re packing to leave, I play "Translife" on my phone. [10] “Enough with traditional Greek music,” I declare to G. “The same songs, again and again! The same sad old lyrics... It’s so boring! The earworms have eaten my brains to death!” I turn up the volume and let myself be carried away by the heart-lightening and spirit-raising synths. The electronic melody transports me back to the ancient stone circle, in Devon last May, where I filmed Othon playing the track live for his video clip.

Here comes the circle again.

Ancient stone circles.

Ancient circle dances.

* * *

The longing for community and belonging is what led me to Queer Spirit festival at Bridwell Park in Devon, a couple of weeks before visiting the island.

At the opening ceremony of the festival, Shokti, one of the organisers, proclaims: “We’re here! We’re queer! We’re cosmic!” – pausing at the end of each sentence to allow the enthusiastic crowd to repeat after him. Shokti continues his speech recounting the purging of queerness under white cisheteropatriarchy and Abrahamic religions, making the case for the naturalness and spirituality of queer people. Over the following days, I attend a plethora of performances, concerts, workshops, and conversations.

As the sun sets on Saturday evening, following a long day spent by the nearby riverbank, I find myself drawn to the fire ceremony. It's 8 pm, and there's still daylight as Al, another founding member of the festival, begins the ceremony by casting a ritual circle in front of a large fire. Their words pay homage to the elements, the folk, and the land. They encourage the congregation to honour our inner fire. They speak about the destructive power of fire and its importance for earth’s renewal. The drums, arranged in a semicircle, respond to their words.

I hear the words and the sounds, but my gaze remains fixed on the fire. The fire is the main performer of this ceremony: rooted in the earth, its flames are like outstretched arms dancing in the air, shooting orange-red sparks up into the sky. It’s powerful, consuming, ferocious. As the night sets in, its presence becomes even more impressive. G and I sit on the grass nearby, surrounded by other people. The air becomes chilly, so we get up and find a spot directly in front of the fire.

Observing the scene around me, I'm struck by the diversity of bodies—varying in race, gender, sexuality, ability, and age. My trans body is only a small part of a greater assemblage of human and nonhuman bodies. Everything is bathed in the orange glow of the fire. Boundaries blur, and even the line between human and nonhuman becomes ambiguous as all these vibrant queer creatures merge with the fire and into the night.

Reflecting the spirit of the fire, Al conducts the ceremony in their polyester shiny orange shirt, red trousers and tie. There's an excessive fabulousness all around. At times, the ceremony, with all its embellishments, appears overdramatised. It has not been repeated countless times, nor has it been practiced for centuries. The details may seem rough, and the patterns unclear. The invocations have not yet acquired the unquestionable status of prayers. The attendees are uncertain of their role and involvement. Yet, amidst this, there's a profound beauty in this uncertainty – a queer ecological experiment of coexistence.

The excessive fabulousness around me reminds me of Timothy Morton’s interpretation of Darwin’s writings, suggesting that life forms are excessive in their display of “non utilitarian gorgeousness” beyond a strict evolutionary purpose. [11]

Al concludes the fire ceremony with an ofering and the opening of the ritual circle. There's movement—a shifting of individuals, some departing, others joining.

As the drummers continue their beat, I find myself deeply immersed in the ritual state.

However, not everyone is in the same mode as I am. In the background, snippets of conversation between two young genderqueer individuals catch my attention: they sound like they have just met, sharing their experiences of coming out, gender identity, sexuality and polyamory. Some others sitting nearby engage in small talk. The music of a punk band blares from a nearby tent.

Despite the distractions,

I remain in the realm of silence,

entranced,

my gaze transfixed by the fire.

Someone adds fresh wood, causing the flames to leap higher.

My body awakens to the rhythm of the drums,

becoming an instrument

that vibrates at each beat.

Moments of ecstasy,

moments of bliss.

I find my inner voice –

a chant beyond language.

Overcoming inhibitions,

I answer the call of the fire – I rise and dance.

My body warms up.

Layers of clothes shed,

one by one,

I’m left in my snake-print dress.

Its heavy fabric anchors me to the ground.

I slide down the top of my dress

and remove my tight long-sleeve top.

Bare-breasted,

my skin glistens in the red light of the fire.

I feel comfortable, powerful and beautiful in my body.

I feel the sexual energy rising,

the heat entering my lungs.

Holding the ends of the fabric,

I lift the dress,

welcoming the heat between my legs.

My arms are reaching skywards,

like flames tongues.

My belly is sticking out provocatively.

I caress it,

I hold it.

My golden egg,

my creative centre.

My hips are a pleasure land,

and my whole body is a dancing flame.

At the same time, the chattering around is endless. A missed opportunity to transcend the confines of language. Verbal dis-communication prevails. The elders ofer no advice, no guidance, no safeguarding of the rites. I hence fold my arms in front of my eyes and enter the portal.

The fire,

the chaotic rhythm of drums,

the ceaseless chattering voices,

the chaos,

the burning of the ancestral home.

Ignorance and indiference,

indiference and pain

intermingle.

It is humanity’s absurdity –

a relentless history of violence,

of destruction.

I witness.

The fire,

great recycler of the world.

The one that brings down cities and civilisations,

monuments and golden statues

and temples

and villages

and forests

and libraries

and villas

and luxury hotels

and forests.

I rejoice in its cathartic energy,

I welcome its sexual force.

G rises. I assist her in shedding her clothes. She only keeps her knickers on.

We dance, slowly.

Our bodies are electrified.

We touch,

we hug,

we kiss.

I contemplate the power of the erotic. Greta Gaard, in her work “Towards a Queer Ecofeminism”, identifies erotophobia as a fundamental issue in Western culture. She envisions a democratic, ecologically aware society where the erotic and sexual diversity are not feared, but embraced and valued. [12]

I sit down, allowing G the space for her own journey.

She is lustful,

she is beautiful,

she is perfect.

There is no lack,

there is no excess.

As darkness descends, more naked bodies join the circle, dancing around the fire. For a moment, I worry that I've stumbled into an eco-hippie camp, but I quickly remind myself that this is Queer Spirit. No predatory masculinity, no essentialist goddess-worshiping femininity, no sexual or gender normativity. This queer circle feels like a sanctuary, ofering a sense of safety, and boundless joy for self-expression—a brief interlude in the chaotic cosmic dance.

In this gathering that questions the notion of norms, we reclaim the colour green and the word ‘natural’ from cisheteropatriarchy. We reclaim rituals. We reclaim the circle.

It is an ongoing experiment, unfixed, imperfect, and unsettled—a tradition in the making.

It is a manifestation of queer and trans ecology, unfolding in the here and now.

—

FOOTNOTES:

1 The traditional festivals in Greece, known as panigyri, have their roots in Ancient Greek festivals that honoured specific gods or deities. Over time, they became integrated into the new Christian religion, resulting in a syncretised form.

2 Kenna, Margaret E. 2017. Greek Island Life: Fieldwork on Anafi. Canon Pyon: Sean Kingston Publishing.

3 Cohen, John. 1988. Pericles in America. Film. Color. 1h 8min.

4 Hopfinger, Sarah. 2018. "Intergenerational performance ecology: a practice-based approach." Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance 23, no. 4: 499- 516 [514].

5 Stone, Sandy. 1991. “The Empire Strikes Back: A Posttransexual Manifesto”. In Body Guards: Cultural Politics of Gender Ambiguity, edited by Julia Epstein and Kristina Straub, 280–304. New York: Routledge. Stryker, Susan. 1994. “My Words to Victor Frankenstein Above the Village of Chamounix: Performing Transgender Rage”. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 1 (3): 237–54.

6 Adams, Tony, Stacy L. Holman Jones, and Carolyn Ellis. 2015. Autoethnography: Understanding Qualitative Research. Oxford University Press, p. 25.

7 Ellis, Carolyn. 2004. The Ethnographic I: A Methodological Novel about Autoethnography. Ethnographic Alternatives Book Series, v. 13. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press, p. xviii.

8 Giulia Casalini's documentary about Va-Bene Elikem Fiatsi is set to be released in 2024.

9 Fynn, Asher. 2022. In This World. Accessed February 20, 2024.

https://vimeo.com/anticswow. 10 Othon. 2023. "TransLife." Accessed February 22, 2024.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=900eL0k1OTI. 11 Morton, Timothy. 2010. The Ecological Thought. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, p. 37,84. 12 Gaard, Greta. 1997. "Toward a Queer Ecofeminism." Hypatia 12, no. 1: 114–137 [115].

2022

We Collectively Published a Special Issue

We Collectively Published a Special Issue

Click on the image to access to the publication.

2021

Elly Clarke & Clareese Hill

Stelly G

Free Bitch

Seán Elder

And still I remain pre-occupied by besideness.

Our bodies sitting, one next to another, differing in posture, poise or stance. A myriad of violences close to them, different violences coming close in different ways. We are listening to a discussion and I wonder if we hear the same things.

We take notes at different points and our attention shifts during the course of it all. You unsheath your pen as I lay mine down.

Whilst beside-ness in itself, may not always be seen as a relation, in the words of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, ‘any child knows who’s shared a bed with siblings. Beside comprises a wide range of desiring, identifying, representing, repelling, paralleling, differentiating, rivalling, leaning, twisting, mimicking, withdrawing, attracting, aggressing, warping, and other relations.’

I sit next to another you, and we are passing through a bealach and there is a voice on the car loudspeaker which asks if you know the name of the dead boy in the forest.

You say no and I know you aren’t telling the truth.

The heather rushing past the windows climbs up into grey rocky cliffs.

You tell me it is beautiful and I agree. We let the mountains form words in our mouths, finding something to talk about other than death.

Footnotes:

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity, Durham, NC: Duke University Press: 2003

Ibid pp: 8

Gaelic word for a mountain pass

It is often this place that was once close to me, and is now distant from me,

if only physically,

besides which I bring myself in writing.

Je trouve des journaux dans lesquels j’ai écrit exclusivement en français pour qu’il soit plus éloigné de moi, ces choses auxquelles j’ai pensé en écrivant. Il semble moins dur dans une langue qui n’est pas la mienne.

I am not attempting to situate myself directly within these spaces when I am writing about them. I am aware of my inability to render myself deep amongst them, amongst memories and amongst performative unfoldings. I do not need to plunge myself under the surface of them. Only to bring myself to some kind of besides, where I can look on to them with both distance and proximity.

Stories in my youth circulate in this place widely and across swathes of land. There are gaps between settlements here large enough and dark enough and seemingly empty enough for peoples’ imaginations to transform otherwise everyday things within the stretches of road with unpolluted sky above it.

There is a theatre in every mouth here.

Footnotes:

4. Annie Ernaux : « Je pars de moi, et je le recouvre par l’écriture », Ouest France, Available here:

https://www.ouest-france.fr/culture/livres/lire-magazine/annie-ernaux-je-pars-de-moi-et-je-le-recouvre-par-l-ecriture-96465a8a-4862-11ec-9fb6-7d55cb1d2c6a

nomi blum

TaPRA Exec Curated Panel 2021 on Institutional (Anti)Racism: Part 2

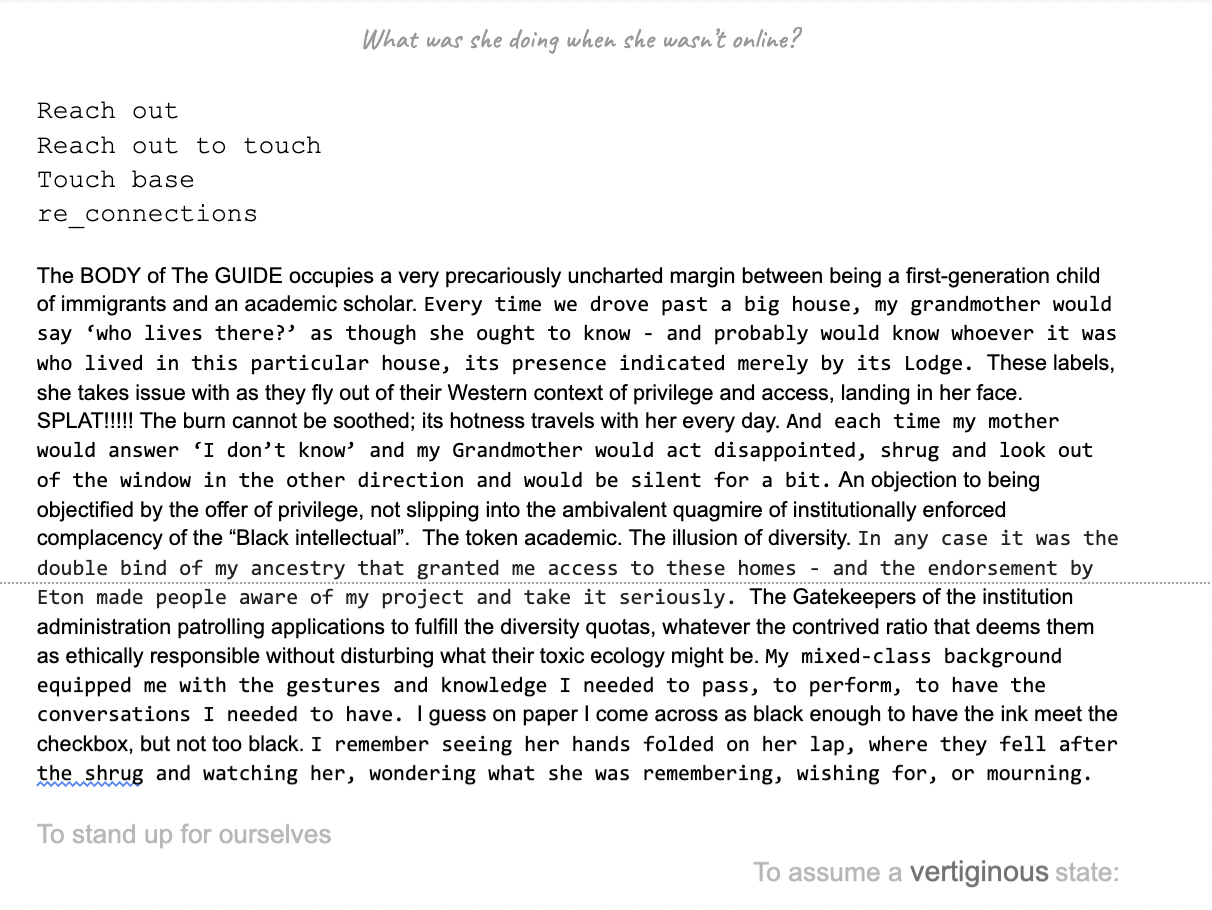

This year’s Exec Curated Panel on Institutional AntiRacism responds to the formation of the Revolution or Nothing network for Black and Global Majority scholars in theatre and performance studies and the collective open letter White Colleague Listen!. The panel seeks to give presence to the affective, embodied, and experiential dimensions of structural racism in Higher Education institutions. The panel explores the dimension of institutional racism that is not easily theorizable: the constant background noise of racial slights, insults, and minimizations that Black, POC, and people of the Global Majority face, despite or perhaps especially in the light of good intentions and gestures to allyship. The curated panel will take two parts – a pre-circulated recorded video podcast with Mojisola Adebayo, Broderick Chow, and Royona Mitra and a live roundtable with Olivia Michiko Gagnon, Tia-Monique Uzor, and melissandre varin.

Lou Sarabadzic

"The opening scene shows a close-up of grass and dandelions. A white line is drawn on the screen, slowly forming the word "Traces" above the grass. The word is written in 3D, floating above the ground. There are then two different sequence shots, visually recorded from the point of view of someone holding the screen.

First sequence shot: The shadow of a white woman with long wavy hair, wearing shiny sandals and a dress, appears on a ground made of beige gravel. As the woman speaks in English, a white line appears on the screen, as if drawn by this woman moving and walking. The line unfolds and carries on as she dances, while the focus remains on the ground, sometimes revealing her feet. After a while, the woman holding the recording screen takes a few steps back, tilts up the screen, which can capture the uninterrupted white line that has been drawn as she was moving. The woman then follows this white line floating above the ground to retrace her steps at a slower pace.

Second sequence shot: A similar scene happens, this time on a vegetal background. We see up in a tree in a park, before the camera comes down to reveal again the same woman's shadow on grass. Again, the woman holding a recording device walks and dances, tracing a white line on the screen, as if she wanted to keep track of her every move. The line is traced up above the ground while she speaks in French. She goes near a bench, an outdoor bin, and then takes a few steps back at the end of to reveal the uninterrupted white line hanging in the air.

The image then fades to black, and credits indicate that the film was created by Lou Sarabadzic, using the app 'Just a Line', iMovie and audacity."

Ashleigh Williams

Sometimes You Gotta Close The Door To Open The Window — Sometimes You Gotta Close The Door To Open The Window is a short film exploring the restrictions of research within academia. Using music videos and live performances as visuals, this film discusses alternative modes of research, and representing marginalised joy. This film was created as part of my New Contemporaries Digital Residency 2021.

babeworld3000@gmail.com @babeworld3000

Annabel Guérédrat

Mami Sargassa

Un conte caribéen futuriste

Par Annabel Guérédrat

(Juin 2021, Cité Internationale des Arts, Paris)

We are in 2083, in a desert island inside the Caribbean area. This island was used to be called (before, a long time ago) : Martinique. But because of the years and centuries of colonization, contamination, occupation and tourism, no human, no animals, no plants exist anymore. Just sargassum, toxic seaweed, had survived.

Manman Dlo did not survy anymore. A new entity, a kind of avatar takes place: who keeps the human form of a woman, genetically modified, stays in this beach during days and nights, nights and days : Manman Sargassa. To keep alive, she is burying herself in sargassum while knowing that this seaweed is a potential health hazard. She is creating the magical act of colonizing in turn this seaweed that was colonizing the human beings who used to live there few years ago. Sargassum have nauseating toxic gases, massively piled up and drying on the beach.

During each ritual burial, Manman Sargassa takes the time to absorb the smell, the swarming of bacteria and other crawling insects scratching her skin.

Through this act of witchcraft, of magic, she’s reborn each time she does it. Day by day, she rehumanize herself. She becomes a heroine, attracted and intimately connected to trash, to this invasive and toxic, contaminating nature.

Mamman Sargassa : a new contaminated heroine in the Caribbean area

Nous sommes en 2083, sur une île déserte dans la mer des Caraïbes. Cette île était appelée Martinique, il y a longtemps. Mais, à cause d’années et de siècles de colonisation, de contamination, d’occupation et de tourisme, aucun humain, aucun animal, aucune plante, n’a survécu. Seules les sargasses, ces algues toxiques, sont restées et ont survécu

Mamman Dlo n’a pas non plus survécu. Une nouvelle entité, sorte d’avatar, l’a remplacé. Qui a gardé l’apparence humaine d’une femme, génétiquement modifiée, qui reste là, sur la plage, jours et nuits, nuits et jours : Mamman Sargassa. Pour rester vivante, elle s’enterre elle-même dans de la sargasse fraiche. Elle créé l’acte magique de coloniser à son tour cette algue qui a colonisé les êtres humains, tout un peuple, qui avait l’habitude de vivre là, des années auparavant. La sargasse toxique dégage des gaz toxiques nauséabonds. A chaque rituel d’enterrement, Mamman Sargassa prend le temps de sentir l’odeur, le grouillement et pullulement d’autres insectes gratter sa peau

A travers cet acte de sorcellerie, de magie, elle renaît autrement, se ré-humanise, jour après jour. Elle devient une héroïne attirée et connectée intimement au trash, à cette nature envahissante et toxique, contaminante

Mamman Sargassa : une nouvelle heroine contaminée dans la region Caraïbes

Sé an lanné 2083 sa fèt. Asou an ti lilèt adan bannzil karayib-la. Non lilèt la sété matinik. Mé apré plizyé lanné boulvès, krim, kolonizasion,pwézonaj, touris, tout pyé bwa, tout zèb, tout lavi té disparèt. Nonm kon zannimo. Sèl bagay ki té tjenbé sé an vyé modèl wawèt yo té bay non sawgas.

Menm Manman Dlo té pèd ta-y la akoz di sa. Sé Mami Wawèt ki té pwan plas li. Tala toujou té ni an koté fanm, épi an ADN mofwazé. I té ka rété bòdlanmè lannuit kon lajounen. Pou i pa mò i té ka maré kòy adan an nich wpèwt fré akondi sé adan an kabann i té yé. I dématé jé-a nan maji pou pran épi viré pwan tout sa wawèt té za pwan yonn dé tan avan. Lidé-y sété di viré pwan pou tay tou sa sé wawèt-la té za tjoué, tout nanm ki té ka viv anlè sawgas la té ni pou sèviy. Wawèt la té ka dégajé an lodè zé pouwi, ki té ka pwézonen épi dékatjé. Sé anlot linivè ki té ka wè jou. Moun pa té jenn wè sa !

Dépi mami wawèt té ka téré kòy an twèl wawèt, ti bèt té ka eklò. Yo té ka fè chyen anlè tout kòy. Yo ka dansé anlè lapoy pou bay an gratèl san fen.

Dépi I fè zafèy-la , i té ka viré mété kòy doubout . I té nèf kon nèf ka ékri. Bouden-y té plen lavi afos manjé sé ti bèt la ki té ka viv anlè sawgas la. I ké ta viré mouné kò-y li yonn. An mitan pwézon-an i té ka tjenbé i té ka fè yonn épi lanvirondaj toksik tala.

Mami Wawèt, Manman Sawgasa, an mètpyès fanm nèf, pwézoné an karayib la.

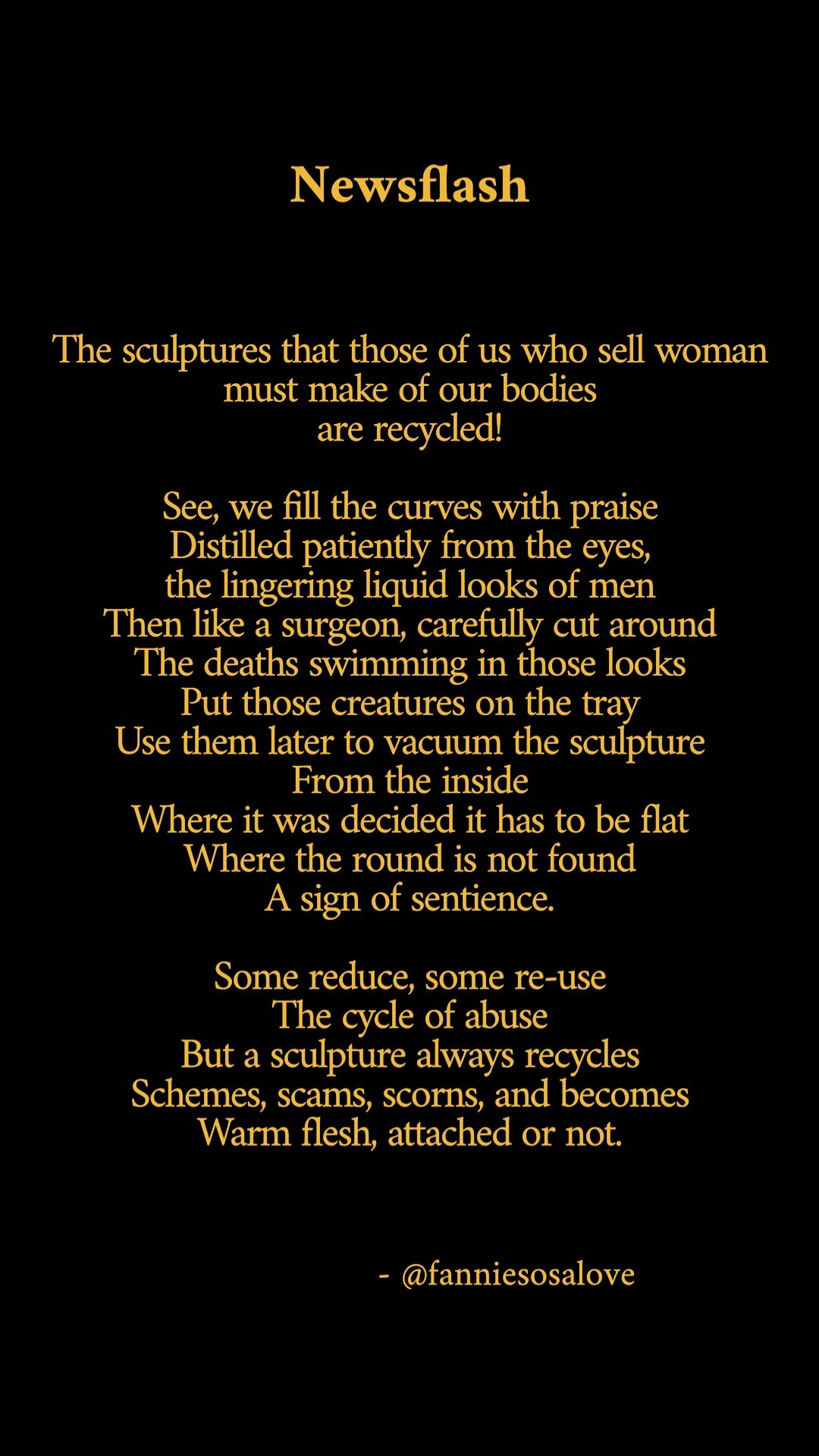

Fannie Sosa

Izdihar Afyouni

A Sermon to Unearth the Wretched

Invocation, rope suspension, ink

2021

-Izdihar Afyouni

@fvckthepost

Big thanks to @cnr.aphilia for rigging and documenting. Thanks to Talie Eigland for final images.

—-

Please feel free to print any or all images in colour or B&W